Iron Age (c. 1800 – 200 BCE)

Vedic period (c. 1500 – 600 BCE)

Starting ca. 1900 BCE, Indo-Aryan tribes moved into the Punjab from Central Asia in several waves of migration.[60][61] The Vedic period is the period when the Vedas were composed, the liturgical hymns from the Indo-Aryan people. The Vedic culture was located in part of north-west India, while other parts of India had a distinct cultural identity during this period. Many regions of the Indian subcontinent transitioned from the Chalcolithic to the Iron Age in this period.[62]

The Vedic culture is described in the texts of Vedas, still sacred to Hindus, which were orally composed and transmitted in Vedic Sanskrit. The Vedas are some of the oldest extant texts in India.[63] The Vedic period, lasting from about 1500 to 500 BCE,[64][65] contributed the foundations of several cultural aspects of the Indian subcontinent.

Vedic society

Historians have analysed the Vedas to posit a Vedic culture in the Punjab region and the upper Gangetic Plain.[62] The peepal tree and cow were sanctified by the time of the Atharva Veda.[67] Many of the concepts of Indian philosophy espoused later, like dharma, trace their roots to Vedic antecedents.[68]

Early Vedic society is described in the Rigveda, the oldest Vedic text, believed to have been compiled during 2nd millennium BCE,[69][70] in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent.[71] At this time, Aryan society consisted of largely tribal and pastoral groups, distinct from the Harappan urbanisation which had been abandoned.[72] The early Indo-Aryan presence probably corresponds, in part, to the Ochre Coloured Pottery culture in archaeological contexts.[73][74]

At the end of the Rigvedic period, the Aryan society began to expand from the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent, into the western Ganges plain. It became increasingly agricultural and was socially organised around the hierarchy of the four varnas, or social classes. This social structure was characterized both by syncretising with the native cultures of northern India,[75] but also eventually by the excluding of some indigenous peoples by labeling their occupations impure.[76] During this period, many of the previous small tribal units and chiefdoms began to coalesce into Janapadas (monarchical, state-level polities).[77]

Janapadas

The Iron Age in the Indian subcontinent from about 1200 BCE to the 6th century BCE is defined by the rise of Janapadas, which are realms, republics and kingdoms—notably the Iron Age Kingdoms of Kuru, Panchala, Kosala, Videha.[78][79]

The Kuru Kingdom (c. 1200–450 BCE) was the first state-level society of the Vedic period, corresponding to the beginning of the Iron Age in northwestern India, around 1200–800 BCE,[80] as well as with the composition of the Atharvaveda (the first Indian text to mention iron, as śyāma ayas, literally "black metal").[81] The Kuru state organised the Vedic hymns into collections, and developed the srauta ritual to uphold the social order.[81] Two key figures of the Kuru state were king Parikshit and his successor Janamejaya, transforming this realm into the dominant political, social, and cultural power of northern Iron Age India.[81] When the Kuru kingdom declined, the centre of Vedic culture shifted to their eastern neighbours, the Panchala kingdom.[81] The archaeological PGW (Painted Grey Ware) culture, which flourished in the Haryana and western Uttar Pradesh regions of northern India from about 1100 to 600 BCE,[73] is believed to correspond to the Kuru and Panchala kingdoms.[81][82]

During the Late Vedic Period, the kingdom of Videha emerged as a new centre of Vedic culture, situated even farther to the East (in what is today Nepal and Bihar state in India);[74] reaching its prominence under the king Janaka, whose court provided patronage for Brahmin sages and philosophers such as Yajnavalkya, Aruni, and Gārgī Vāchaknavī.[83] The later part of this period corresponds with a consolidation of increasingly large states and kingdoms, called Mahajanapadas, all across Northern India.

Second urbanisation (c. 600 – 200 BCE)

Sometime between 800 and 200 BCE the Śramaṇa movement formed, from which originated Jainism and Buddhism. In the same period, the first Upanishads were written. After 500 BCE, the so-called "second urbanisation" started, with new urban settlements arising at the Ganges plain, especially the Central Ganges plain.[84] The foundations for the "second urbanisation" were laid prior to 600 BCE, in the Painted Grey Ware culture of the Ghaggar-Hakra and Upper Ganges Plain; although most PGW sites were small farming villages, "several dozen" PGW sites eventually emerged as relatively large settlements that can be characterized as towns, the largest of which were fortified by ditches or moats and embankments made of piled earth with wooden palisades, albeit smaller and simpler than the elaborately fortified large cities which grew after 600 BCE in the Northern Black Polished Ware culture.[85]

The Central Ganges Plain, where Magadha gained prominence, forming the base of the Maurya Empire, was a distinct cultural area,[86] with new states arising after 500 BCE[87] during the so-called "second urbanisation".[88][note 2] It was influenced by the Vedic culture,[89] but differed markedly from the Kuru-Panchala region.[86] It "was the area of the earliest known cultivation of rice in South Asia and by 1800 BCE was the location of an advanced Neolithic population associated with the sites of Chirand and Chechar".[90] In this region, the Śramaṇic movements flourished, and Jainism and Buddhism originated.[84]

Buddhism and Jainism

The time between 800 BCE and 400 BCE witnessed the composition of the earliest Upanishads.[4][91][92] The Upanishads form the theoretical basis of classical Hinduism, and are also known as Vedanta (conclusion of the Vedas).[93]

Increasing urbanisation of India in 7th and 6th centuries BCE led to the rise of new ascetic or "Śramaṇa movements" which challenged the orthodoxy of rituals.[4] Mahavira (c. 549–477 BCE), proponent of Jainism, and Gautama Buddha (c. 563–483 BCE), founder of Buddhism, were the most prominent icons of this movement. Śramaṇa gave rise to the concept of the cycle of birth and death, the concept of samsara, and the concept of liberation.[94] Buddha found a Middle Way that ameliorated the extreme asceticism found in the Śramaṇa religions.[95]

Around the same time, Mahavira (the 24th Tirthankara in Jainism) propagated a theology that was to later become Jainism.[96] However, Jain orthodoxy believes the teachings of the Tirthankaras predates all known time and scholars believe Parshvanatha (c. 872 – c. 772 BCE), accorded status as the 23rd Tirthankara, was a historical figure. The Vedas are believed to have documented a few Tirthankaras and an ascetic order similar to the Śramaṇa movement.[97]

Sanskrit epics

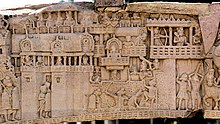

The Sanskrit epics Ramayana and Mahabharata were composed during this period.[98] The Mahabharata remains, till this day, the longest single poem in the world.[99] Historians formerly postulated an "epic age" as the milieu of these two epic poems, but now recognize that the texts (which are both familiar with each other) went through multiple stages of development over centuries. For instance, the Mahabharata may have been based on a small-scale conflict (possibly about 1000 BCE) which was eventually "transformed into a gigantic epic war by bards and poets". There is no conclusive proof from archaeology as to whether the specific events of the Mahabharata have any historical basis.[100] The existing texts of these epics are believed to belong to the post-Vedic age, between c. 400 BCE and 400 CE.[100][101]

Mahajanapadas

The period from c. 600 BCE to c. 300 BCE witnessed the rise of the Mahajanapadas, sixteen powerful and vast kingdoms and oligarchic republics. These Mahajanapadas evolved and flourished in a belt stretching from Gandhara in the northwest to Bengal in the eastern part of the Indian subcontinent and included parts of the trans-Vindhyan region.[102] Ancient Buddhist texts, like the Aṅguttara Nikāya,[103] make frequent reference to these sixteen great kingdoms and republics—Anga, Assaka, Avanti, Chedi, Gandhara, Kashi, Kamboja, Kosala, Kuru, Magadha, Malla, Matsya (or Machcha), Panchala, Surasena, Vṛji, and Vatsa. This period saw the second major rise of urbanism in India after the Indus Valley Civilisation.[104]

Early "republics" or gaṇasaṅgha,[105] such as Shakyas, Koliyas, Mallakas, and Licchavis had republican governments. Gaṇasaṅghas,[105] such as the Mallakas, centered in the city of Kusinagara, and the Vajjika League, centered in the city of Vaishali, existed as early as the 6th century BCE and persisted in some areas until the 4th century CE.[106] The most famous clan amongst the ruling confederate clans of the Vajji Mahajanapada were the Licchavis.[107]

This period corresponds in an archaeological context to the Northern Black Polished Ware culture. Especially focused in the Central Ganges plain but also spreading across vast areas of the northern and central Indian subcontinent, this culture is characterized by the emergence of large cities with massive fortifications, significant population growth, increased social stratification, wide-ranging trade networks, construction of public architecture and water channels, specialized craft industries (e.g., ivory and carnelian carving), a system of weights, punch-marked coins, and the introduction of writing in the form of Brahmi and Kharosthi scripts.[108][109] The language of the gentry at that time was Sanskrit, while the languages of the general population of northern India are referred to as Prakrits.

Many of the sixteen kingdoms had coalesced into four major ones by 500/400 BCE, by the time of Gautama Buddha. These four were Vatsa, Avanti, Kosala, and Magadha. The life of Gautama Buddha was mainly associated with these four kingdoms.[104]

Early Magadha dynasties

Magadha formed one of the sixteen Mahajanapadas (Sanskrit: "Great Realms") or kingdoms in ancient India. The core of the kingdom was the area of Bihar south of the Ganges; its first capital was Rajagriha (modern Rajgir) then Pataliputra (modern Patna). Magadha expanded to include most of Bihar and Bengal with the conquest of Licchavi and Anga respectively,[110] followed by much of eastern Uttar Pradesh and Orissa. The ancient kingdom of Magadha is heavily mentioned in Jain and Buddhist texts. It is also mentioned in the Ramayana, Mahabharata and Puranas.[111] The earliest reference to the Magadha people occurs in the Atharva-Veda where they are found listed along with the Angas, Gandharis, and Mujavats. Magadha played an important role in the development of Jainism and Buddhism. The Magadha kingdom included republican communities such as the community of Rajakumara. Villages had their own assemblies under their local chiefs called Gramakas. Their administrations were divided into executive, judicial, and military functions.

Early sources, from the Buddhist Pāli Canon, the Jain Agamas and the Hindu Puranas, mention Magadha being ruled by the Pradyota dynasty and Haryanka dynasty (c. 544–413 BCE) for some 200 years, c. 600–413 BCE. King Bimbisara of the Haryanka dynasty led an active and expansive policy, conquering Anga in what is now eastern Bihar and West Bengal. King Bimbisara was overthrown and killed by his son, Prince Ajatashatru, who continued the expansionist policy of Magadha. During this period, Gautama Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, lived much of his life in Magadha kingdom. He attained enlightenment in Bodh Gaya, gave his first sermon in Sarnath and the first Buddhist council was held in Rajgriha.[112] The Haryanka dynasty was overthrown by the Shaishunaga dynasty (c. 413–345 BCE). The last Shishunaga ruler, Kalasoka, was assassinated by Mahapadma Nanda in 345 BCE, the first of the so-called Nine Nandas, which were Mahapadma and his eight sons.

Nanda Empire and Alexander's campaign

The Nanda Empire (c. 345–322 BCE), at its greatest extent, extended from Bengal in the east, to the Punjab region in the west and as far south as the Vindhya Range.[113] The Nanda dynasty was famed for their great wealth. The Nanda dynasty built on the foundations laid by their Haryanka and Shishunaga predecessors to create the first great empire of north India.[114] To achieve this objective they built a vast army, consisting of 200,000 infantry, 20,000 cavalry, 2,000 war chariots and 3,000 war elephants (at the lowest estimates).[115][116][117] According to the Greek historian Plutarch, the size of the Nanda army was even larger, numbering 200,000 infantry, 80,000 cavalry, 8,000 war chariots, and 6,000 war elephants.[116][118] However, the Nanda Empire did not have the opportunity to see their army face Alexander the Great, who invaded north-western India at the time of Dhana Nanda, since Alexander was forced to confine his campaign to the plains of Punjab and Sindh, for his forces mutinied at the river Beas and refused to go any further upon encountering Nanda and Gangaridai forces.[116]

Maurya Empire

The Maurya Empire (322–185 BCE) unified most of the Indian subcontinent into one state, and was the largest empire ever to exist on the Indian subcontinent.[119] At its greatest extent, the Mauryan Empire stretched to the north up to the natural boundaries of the Himalayas and to the east into what is now Assam. To the west, it reached beyond modern Pakistan, to the Hindu Kush mountains in what is now Afghanistan. The empire was established by Chandragupta Maurya assisted by Chanakya (Kautilya) in Magadha (in modern Bihar) when he overthrew the Nanda Empire.[120]

Chandragupta rapidly expanded his power westwards across central and western India, and by 317 BCE the empire had fully occupied Northwestern India. The Mauryan Empire then defeated Seleucus I, a diadochus and founder of the Seleucid Empire, during the Seleucid–Mauryan war, thus gained additional territory west of the Indus River. Chandragupta's son Bindusara succeeded to the throne around 297 BCE. By the time he died in c. 272 BCE, a large part of the Indian subcontinent was under Mauryan suzerainty. However, the region of Kalinga (around modern day Odisha) remained outside Mauryan control, perhaps interfering with their trade with the south.[121]

Bindusara was succeeded by Ashoka, whose reign lasted for around 37 years until his death in about 232 BCE.[122] His campaign against the Kalingans in about 260 BCE, though successful, led to immense loss of life and misery. This filled Ashoka with remorse and led him to shun violence, and subsequently to embrace Buddhism.[121] The empire began to decline after his death and the last Mauryan ruler, Brihadratha, was assassinated by Pushyamitra Shunga to establish the Shunga Empire.[122]

Under Chandragupta Maurya and his successors, internal and external trade, agriculture, and economic activities all thrived and expanded across India thanks to the creation of a single efficient system of finance, administration, and security. The Mauryans built the Grand Trunk Road, one of Asia's oldest and longest major roads connecting the Indian subcontinent with Central Asia.[123] After the Kalinga War, the Empire experienced nearly half a century of peace and security under Ashoka. Mauryan India also enjoyed an era of social harmony, religious transformation, and expansion of the sciences and of knowledge. Chandragupta Maurya's embrace of Jainism increased social and religious renewal and reform across his society, while Ashoka's embrace of Buddhism has been said to have been the foundation of the reign of social and political peace and non-violence across all of India. Ashoka sponsored the spreading of Buddhist missionaries into Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia, West Asia, North Africa, and Mediterranean Europe.[124]

The Arthashastra wrote by Chanakya and the Edicts of Ashoka are the primary written records of the Mauryan times. Archaeologically, this period falls into the era of Northern Black Polished Ware. The Mauryan Empire was based on a modern and efficient economy and society. However, the sale of merchandise was closely regulated by the government.[125] Although there was no banking in the Mauryan society, usury was customary. A significant amount of written records on slavery are found, suggesting a prevalence thereof.[126] During this period, a high quality steel called Wootz steel was developed in south India and was later exported to China and Arabia.[8]

Sangam period

During the Sangam period Tamil literature flourished from the 3rd century BCE to the 4th century CE. During this period, three Tamil dynasties, collectively known as the Three Crowned Kings of Tamilakam: Chera dynasty, Chola dynasty, and the Pandya dynasty ruled parts of southern India.[128]

The Sangam literature deals with the history, politics, wars, and culture of the Tamil people of this period.[129] The scholars of the Sangam period rose from among the common people who sought the patronage of the Tamil Kings, but who mainly wrote about the common people and their concerns.[130] Unlike Sanskrit writers who were mostly Brahmins, Sangam writers came from diverse classes and social backgrounds and were mostly non-Brahmins. They belonged to different faiths and professions such as farmers, artisans, merchants, monks, and priests, including also royalty and women.[130]

Around c. 300 BCE – c. 200 CE, Pathupattu, an anthology of ten mid-length books collection, which is considered part of Sangam Literature, were composed; the composition of eight anthologies of poetic works Ettuthogai as well as the composition of eighteen minor poetic works Patiṉeṇkīḻkaṇakku; while Tolkāppiyam, the earliest grammarian work in the Tamil language was developed.[131] Also, during Sangam period, two of the Five Great Epics of Tamil Literature were composed. Ilango Adigal composed Silappatikaram, which is a non-religious work, that revolves around Kannagi, who having lost her husband to a miscarriage of justice at the court of the Pandyan dynasty, wreaks her revenge on his kingdom,[132] and Manimekalai, composed by Chithalai Chathanar, is a sequel to Silappatikaram, and tells the story of the daughter of Kovalan and Madhavi, who became a Buddhist Bikkuni.[133][134]

Comments

Post a Comment