Early modern period (c. 1526–1858 CE)

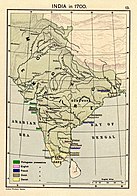

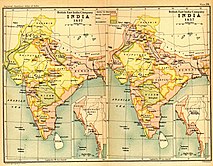

The early modern period of Indian history is dated from 1526 CE to 1858 CE, corresponding to the rise and fall of the Mughal Empire, which inherited from the Timurid Renaissance. During this age India's economy expanded, relative peace was maintained and arts were patronized. This period witnessed the further development of Indo-Islamic architecture;[314][315] the growth of Mahrattas and Sikhs enabled them to rule significant regions of India in the waning days of the Mughal empire, which formally came to an end when the British Raj was founded.[22] With the discovery of the Cape route in the 1500s, the first Europeans to arrive by sea and establish themselves, were the Portuguese in Goa and Bombay.[316]

Mughal Empire

In 1526, Babur, a Timurid descendant of Timur and Genghis Khan from Fergana Valley (modern day Uzbekistan), swept across the Khyber Pass and established the Mughal Empire, which at its zenith covered much of South Asia.[318] However, his son Humayun was defeated by the Afghan warrior Sher Shah Suri in the year 1540, and Humayun was forced to retreat to Kabul. After Sher Shah's death, his son Islam Shah Suri and his Hindu general Hemu Vikramaditya established secular rule in North India from Delhi until 1556, when Akbar (r. 1556–1605), grandson of Babur, defeated Hemu in the Second Battle of Panipat on 6 November 1556 after winning Battle of Delhi. Akbar tried to establish a good relationship with the Hindus. Akbar declared "Amari" or non-killing of animals in the holy days of Jainism. He rolled back the jizya tax for non-Muslims. The Mughal emperors married local royalty, allied themselves with local maharajas, and attempted to fuse their Turko-Persian culture with ancient Indian styles, creating a unique Indo-Persian culture and Indo-Saracenic architecture.

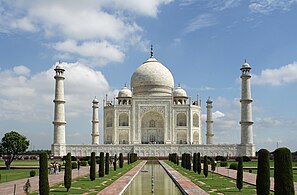

Akbar married a Rajput princess, Mariam-uz-Zamani, and they had a son, Jahangir (r. 1605–1627), who was part-Mughal and part-Rajput, as were future Mughal emperors.[319] Jahangir more or less followed his father's policy. The Mughal dynasty ruled most of the Indian subcontinent by 1600. The reign of Shah Jahan (r. 1628–1658) was the golden age of Mughal architecture. He erected several large monuments, the most famous of which is the Taj Mahal at Agra, as well as the Moti Masjid in Agra, the Red Fort, the Jama Masjid, Delhi, and the Lahore Fort.

It was one of the largest empires to have existed in the Indian subcontinent,[320] and surpassed China to become the world's largest economic power, controlling 24.4% of the world economy,[321] and the world leader in manufacturing,[322] producing 25% of global industrial output.[323] The economic and demographic upsurge was stimulated by Mughal agrarian reforms that intensified agricultural production,[324] a proto-industrializing economy that began moving towards industrial manufacturing,[325] and a relatively high degree of urbanisation for its time.[326]

The Mughal Empire reached the zenith of its territorial expanse during the reign of Aurangzeb (r. 1658–1707), under whose reign the proto-industrialization[327] was waved and India surpassed Qing China in becoming the world's largest economy.[328][329] Aurangzeb was less tolerant than his predecessors, reintroducing the jizya tax and destroying several historical temples, while at the same time building more Hindu temples than he destroyed,[330] employing significantly more Hindus in his imperial bureaucracy than his predecessors, and advancing administrators based on their ability rather than their religion.[331] However, he is often blamed for the erosion of the tolerant syncretic tradition of his predecessors, as well as increasing religious controversy and centralisation. The English East India Company suffered a defeat at the Anglo-Mughal War.[332][333]

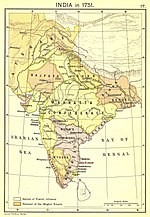

The empire went into decline thereafter. The Mughals suffered several blows due to invasions from Marathas, Rajputs, Jats and Afghans. In 1737, the Maratha general Bajirao of the Maratha Empire invaded and plundered Delhi. Under the general Amir Khan Umrao Al Udat, the Mughal Emperor sent 8,000 troops to drive away the 5,000 Maratha cavalry soldiers. Baji Rao, however, easily routed the novice Mughal general and the rest of the imperial Mughal army fled. In 1737, in the final defeat of Mughal Empire, the commander-in-chief of the Mughal Army, Nizam-ul-mulk, was routed at Bhopal by the Maratha army. This essentially brought an end to the Mughal Empire. While Bharatpur State under Jat ruler Suraj Mal, overran the Mughal garrison at Agra and plundered the city taking with them the two great silver doors of the entrance of the famous Taj Mahal; which were then melted down by Suraj Mal in 1761.[334] In 1739, Nader Shah, emperor of Iran, defeated the Mughal army at the Battle of Karnal.[335] After this victory, Nader captured and sacked Delhi, carrying away many treasures, including the Peacock Throne.[336] Mughal rule was further weakened by constant native Indian resistance; Banda Singh Bahadur led the Sikh Khalsa against Mughal religious oppression; Hindu Rajas of Bengal, Pratapaditya and Raja Sitaram Ray revolted; and Maharaja Chhatrasal, of Bundela Rajputs, fought the Mughals and established the Panna State.[337] The Mughal dynasty was reduced to puppet rulers by 1757. Vadda Ghalughara took place under the Muslim provincial government based at Lahore to wipe out the Sikhs, with 30,000 Sikhs being killed, an offensive that had begun with the Mughals, with the Chhota Ghallughara,[338] and lasted several decades under its Muslim successor states.[339]

Marathas and Sikhs

Maratha Empire

The Maratha kingdom was founded and consolidated by Chatrapati Shivaji, a Maratha aristocrat of the Bhonsle clan.[340] However, the credit for making the Marathas formidable power nationally goes to Peshwa (chief minister) Bajirao I. Historian K.K. Datta wrote that Bajirao I "may very well be regarded as the second founder of the Maratha Empire".[341]

In the early 18th century, under the Peshwas, the Marathas consolidated and ruled over much of South Asia. The Marathas are credited to a large extent for ending Mughal rule in India.[342][343][344] In 1737, the Marathas defeated a Mughal army in their capital, in the Battle of Delhi. The Marathas continued their military campaigns against the Mughals, Nizam, Nawab of Bengal and the Durrani Empire to further extend their boundaries. By 1760, the domain of the Marathas stretched across most of the Indian subcontinent.[citation needed] The Marathas even attempted to capture Delhi and discussed putting Vishwasrao Peshwa on the throne there in place of the Mughal emperor.[345]

The Maratha empire at its peak stretched from Tamil Nadu[346] in the south, to Peshawar (modern-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan[347] [note 3]) in the north, and Bengal in the east. The Northwestern expansion of the Marathas was stopped after the Third Battle of Panipat (1761). However, the Maratha authority in the north was re-established within a decade under Peshwa Madhavrao I.[349]

Under Madhavrao I, the strongest knights were granted semi-autonomy, creating a confederacy of United Maratha states under the Gaekwads of Baroda, the Holkars of Indore and Malwa, the Scindias of Gwalior and Ujjain, the Bhonsales of Nagpur and the Puars of Dhar and Dewas. In 1775, the East India Company intervened in a Peshwa family succession struggle in Pune, which led to the First Anglo-Maratha War, resulting in a Maratha victory.[350] The Marathas remained a major power in India until their defeat in the Second and Third Anglo-Maratha Wars (1805–1818), which resulted in the East India Company controlling most of India.

Sikh Empire

The Sikh Empire, ruled by members of the Sikh religion, was a political entity that governed the Northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent. The empire, based around the Punjab region, existed from 1799 to 1849. It was forged, on the foundations of the Khalsa, under the leadership of Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1780–1839) from an array of autonomous Punjabi Misls of the Sikh Confederacy.[citation needed]

Maharaja Ranjit Singh consolidated many parts of northern India into an empire. He primarily used his Sikh Khalsa Army that he trained in European military techniques and equipped with modern military technologies. Ranjit Singh proved himself to be a master strategist and selected well-qualified generals for his army. He continuously defeated the Afghan armies and successfully ended the Afghan-Sikh Wars. In stages, he added central Punjab, the provinces of Multan and Kashmir, and the Peshawar Valley to his empire.[352][353]

At its peak, in the 19th century, the empire extended from the Khyber Pass in the west, to Kashmir in the north, to Sindh in the south, running along Sutlej river to Himachal in the east. After the death of Ranjit Singh, the empire weakened, leading to conflict with the British East India Company. The hard-fought First Anglo-Sikh War and Second Anglo-Sikh War marked the downfall of the Sikh Empire, making it among the last areas of the Indian subcontinent to be conquered by the British.

Other kingdoms

The Kingdom of Mysore in southern India expanded to its greatest extent under Hyder Ali and his son Tipu Sultan in the later half of the 18th century. Under their rule, Mysore fought series of wars against the Marathas and British or their combined forces. The Maratha–Mysore War ended in April 1787, following the finalizing of treaty of Gajendragad, in which, Tipu Sultan was obligated to pay tribute to the Marathas. Concurrently, the Anglo-Mysore Wars took place, where the Mysoreans used the Mysorean rockets. The Fourth Anglo-Mysore War (1798–1799) saw the death of Tipu. Mysore's alliance with the French was seen as a threat to the British East India Company, and Mysore was attacked from all four sides. The Nizam of Hyderabad and the Marathas launched an invasion from the north. The British won a decisive victory at the Siege of Seringapatam (1799).

Hyderabad was founded by the Qutb Shahi dynasty of Golconda in 1591. Following a brief Mughal rule, Asif Jah, a Mughal official, seized control of Hyderabad and declared himself Nizam-al-Mulk of Hyderabad in 1724. The Nizams lost considerable territory and paid tribute to the Maratha Empire after being routed in multiple battles, such as the Battle of Palkhed.[354] However, the Nizams maintained their sovereignty from 1724 until 1948 through paying tributes to the Marathas, and later, being vassels of the British. Hyderabad State became a princely state in British India in 1798.

The Nawabs of Bengal had become the de facto rulers of Bengal following the decline of Mughal Empire. However, their rule was interrupted by Marathas who carried out six expeditions in Bengal from 1741 to 1748, as a result of which Bengal became a tributary state of Marathas. On 23 June 1757, Siraj ud-Daulah, the last independent Nawab of Bengal was betrayed in the Battle of Plassey by Mir Jafar. He lost to the British, who took over the charge of Bengal in 1757, installed Mir Jafar on the Masnad (throne) and established itself to a political power in Bengal.[355] In 1765 the system of Dual Government was established, in which the Nawabs ruled on behalf of the British and were mere puppets to the British. In 1772 the system was abolished and Bengal was brought under the direct control of the British. In 1793, when the Nizamat (governorship) of the Nawab was also taken away from them, they remained as the mere pensioners of the British East India Company.[356][357]

In the 18th century, the whole of Rajputana was virtually subdued by the Marathas. The Second Anglo-Maratha War distracted the Marathas from 1807 to 1809, but afterward Maratha domination of Rajputana resumed. In 1817, the British went to war with the Pindaris, raiders who were fled in Maratha territory, which quickly became the Third Anglo-Maratha War, and the British government offered its protection to the Rajput rulers from the Pindaris and the Marathas. By the end of 1818 similar treaties had been executed between the other Rajput states and Britain. The Maratha Sindhia ruler of Gwalior gave up the district of Ajmer-Merwara to the British, and Maratha influence in Rajasthan came to an end.[358] Most of the Rajput princes remained loyal to Britain in the Revolt of 1857, and few political changes were made in Rajputana until Indian independence in 1947. The Rajputana Agency contained more than 20 princely states, most notable being Udaipur State, Jaipur State, Bikaner State and Jodhpur State.

After the fall of the Maratha Empire, many Maratha dynasties and states became vassals in a subsidiary alliance with the British, to form the largest bloc of princely states in the British Raj, in terms of territory and population.[citation needed] With the decline of the Sikh Empire, after the First Anglo-Sikh War in 1846, under the terms of the Treaty of Amritsar, the British government sold Kashmir to Maharaja Gulab Singh and the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir, the second-largest princely state in British India, was created by the Dogra dynasty.[359][360] While in Eastern and Northeastern India, the Hindu and Buddhist states of Cooch Behar Kingdom, Twipra Kingdom and Kingdom of Sikkim were annexed by the British and made vassal princely state.

After the fall of the Vijayanagara Empire, Polygar states emerged in Southern India; and managed to weather invasions and flourished until the Polygar Wars, where they were defeated by the British East India Company forces.[361] Around the 18th century, the Kingdom of Nepal was formed by Rajput rulers.[362]

European exploration

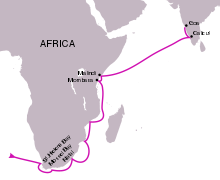

In 1498, a Portuguese fleet under Vasco da Gama discovered a new sea route from Europe to India, which paved the way for direct Indo-European commerce. The Portuguese soon set up trading posts in Velha Goa, Damaon, Dio island, and Bombay. After their conquest in Goa, the Portuguese instituted the Goa Inquisition, where new Indian converts were punished for suspected heresy against Christianity and non-Christians were condemned for discouraging those considering conversion or for convincing others to renounce Christianity.[363] Goa remained the main Portuguese territory until it was annexed by India in 1961.[364][page needed]

The next to arrive were the Dutch, with their main base in Ceylon. They established ports in Malabar. However, their expansion into India was halted after their defeat in the Battle of Colachel by the Kingdom of Travancore during the Travancore-Dutch War. The Dutch never recovered from the defeat and no longer posed a large colonial threat to India.[365][366]

The internal conflicts among Indian kingdoms gave opportunities to the European traders to gradually establish political influence and appropriate lands. Following the Dutch, the British—who set up in the west coast port of Surat in 1619—and the French both established trading outposts in India. Although these continental European powers controlled various coastal regions of southern and eastern India during the ensuing century, they eventually lost all their territories in India to the British, with the exception of the French outposts of Pondichéry and Chandernagore,[367][368] and the Portuguese colonies of Goa, Damaon& Diu.[369]

East India Company rule in India

The English East India Company was founded in 1600 as The Company of Merchants of London Trading into the East Indies. It gained a foothold in India with the establishment of a factory in Masulipatnam on the Eastern coast of India in 1611 and a grant of rights by the Mughal emperor Jahangir to establish a factory in Surat in 1612. In 1640, after receiving similar permission from the Vijayanagara ruler farther south, a second factory was established in Madras on the southeastern coast. The islet of Bom Bahia in present-day Mumbai (Bombay), was a Portuguese outpost not far from Surat, it was presented to Charles II of England as dowry, in his marriage to Catherine of Braganza, Charles in turn leased Bombay to the Company in 1668. Two decades later, the company established a trade post in the River Ganges delta, when a factory was set up in Calcutta (Kolkata). During this time other companies established by the Portuguese, Dutch, French, and Danish were similarly expanding in the sub-continent.

The company's victory under Robert Clive in the 1757 Battle of Plassey and another victory in the 1764 Battle of Buxar (in Bihar), consolidated the company's power, and forced emperor Shah Alam II to appoint it the diwan, or revenue collector, of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. The company thus became the de facto ruler of large areas of the lower Gangetic plain by 1773. It also proceeded by degrees to expand its dominions around Bombay and Madras. The Anglo-Mysore Wars (1766–99) and the Anglo-Maratha Wars (1772–1818) left it in control of large areas of India south of the Sutlej River. With the defeat of the Marathas, no native power represented a threat for the company any longer.[370]

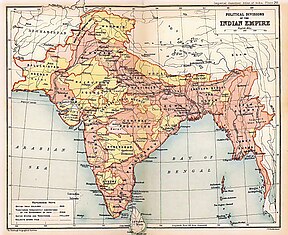

The expansion of the company's power chiefly took two forms. The first of these was the outright annexation of Indian states and subsequent direct governance of the underlying regions that collectively came to comprise British India. The annexed regions included the North-Western Provinces (comprising Rohilkhand, Gorakhpur, and the Doab) (1801), Delhi (1803), Assam (Ahom Kingdom 1828) and Sindh (1843). Punjab, North-West Frontier Province, and Kashmir were annexed after the Anglo-Sikh Wars in 1849–56 (Period of tenure of Marquess of Dalhousie Governor General). However, Kashmir was immediately sold under the Treaty of Amritsar (1850) to the Dogra Dynasty of Jammu and thereby became a princely state. In 1854, Berar was annexed along with the state of Oudh two years later.[371]

The second form of asserting power involved treaties in which Indian rulers acknowledged the company's hegemony in return for limited internal autonomy. Since the company operated under financial constraints, it had to set up political underpinnings for its rule.[372] The most important such support came from the subsidiary alliances with Indian princes during the first 75 years of Company rule.[372] In the early 19th century, the territories of these princes accounted for two-thirds of India.[372] When an Indian ruler who was able to secure his territory wanted to enter such an alliance, the company welcomed it as an economical method of indirect rule that did not involve the economic costs of direct administration or the political costs of gaining the support of alien subjects.[373]

In return, the company undertook the "defense of these subordinate allies and treated them with traditional respect and marks of honor."[373] Subsidiary alliances created the Princely States of the Hindu maharajas and the Muslim nawabs. Prominent among the princely states were Cochin (1791), Jaipur (1794), Travancore (1795), Hyderabad (1798), Mysore (1799), Cis-Sutlej Hill States (1815), Central India Agency (1819), Cutch and Gujarat Gaikwad territories (1819), Rajputana (1818) and Bahawalpur (1833).[371]

Indian indenture system

The Indian indenture system was an ongoing system of indenture, a form of debt bondage, by which 3.5 million Indians were transported to various colonies of European powers to provide labor for the (mainly sugar) plantations. It started from the end of slavery in 1833 and continued until 1920. This resulted in the development of a large Indian diaspora that spread from the Caribbean (e.g. Trinidad and Tobago) to the Pacific Ocean (e.g. Fiji) and the growth of large Indo-Caribbean and Indo-African populations.

Modern period and independence (after c. 1850 CE)

Rebellion of 1857 and its consequences

The Indian rebellion of 1857 was a large-scale rebellion by soldiers employed by the British East India Company in northern and central India against the company's rule. The spark that led to the mutiny was the issue of new gunpowder cartridges for the Enfield rifle, which was insensitive to local religious prohibition. The key mutineer was Mangal Pandey.[374] In addition, the underlying grievances over British taxation, the ethnic gulf between the British officers and their Indian troops and land annexations played a significant role in the rebellion. Within weeks after Pandey's mutiny, dozens of units of the Indian army joined peasant armies in widespread rebellion. The rebel soldiers were later joined by Indian nobility, many of whom had lost titles and domains under the Doctrine of Lapse and felt that the company had interfered with a traditional system of inheritance. Rebel leaders such as Nana Sahib and the Rani of Jhansi belonged to this group.[375]

After the outbreak of the mutiny in Meerut, the rebels very quickly reached Delhi. The rebels had also captured large tracts of the North-Western Provinces and Awadh (Oudh). Most notably, in Awadh, the rebellion took on the attributes of a patriotic revolt against British presence.[376] However, the British East India Company mobilised rapidly with the assistance of friendly Princely states, but it took the British the remainder of 1857 and the better part of 1858 to suppress the rebellion. Due to the rebels being poorly equipped and having no outside support or funding, they were brutally subdued by the British.[377]

In the aftermath, all power was transferred from the British East India Company to the British Crown, which began to administer most of India as a number of provinces. The Crown controlled the company's lands directly and had considerable indirect influence over the rest of India, which consisted of the Princely states ruled by local royal families. There were officially 565 princely states in 1947, but only 21 had actual state governments, and only three were large (Mysore, Hyderabad, and Kashmir). They were absorbed into the independent nation in 1947–48.[378]

British Raj (1858–1947)

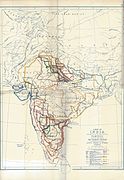

After 1857, the colonial government strengthened and expanded its infrastructure via the court system, legal procedures, and statutes. The Indian Penal Code came into being.[379] In education, Thomas Babington Macaulay had made schooling a priority for the Raj in his famous minute of February 1835 and succeeded in implementing the use of English as the medium of instruction. By 1890 some 60,000 Indians had matriculated.[380] The Indian economy grew at about 1% per year from 1880 to 1920, and the population also grew at 1%. However, from 1910s Indian private industry began to grow significantly. India built a modern railway system in the late 19th century which was the fourth largest in the world.[381] The British Raj invested heavily in infrastructure, including canals and irrigation systems in addition to railways, telegraphy, roads and ports.[382] However, historians have been bitterly divided on issues of economic history, with the Nationalist school arguing that India was poorer at the end of British rule than at the beginning and that impoverishment occurred because of the British.[383]

In 1905, Lord Curzon split the large province of Bengal into a largely Hindu western half and "Eastern Bengal and Assam", a largely Muslim eastern half. The British goal was said to be for efficient administration but the people of Bengal were outraged at the apparent "divide and rule" strategy. It also marked the beginning of the organised anti-colonial movement. When the Liberal party in Britain came to power in 1906, he was removed. Bengal was reunified in 1911. The new Viceroy Gilbert Minto and the new Secretary of State for India John Morley consulted with Congress leaders on political reforms. The Morley-Minto reforms of 1909 provided for Indian membership of the provincial executive councils as well as the Viceroy's executive council. The Imperial Legislative Council was enlarged from 25 to 60 members and separate communal representation for Muslims was established in a dramatic step towards representative and responsible government.[384] Several socio-religious organisations came into being at that time. Muslims set up the All India Muslim League in 1906. It was not a mass party but was designed to protect the interests of the aristocratic Muslims. It was internally divided by conflicting loyalties to Islam, the British, and India, and by distrust of Hindus.[citation needed] The Hindu Mahasabha and Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) sought to represent Hindu interests though the latter always claimed it to be a "cultural" organisation.[385] Sikhs founded the Shiromani Akali Dal in 1920.[386] However, the largest and oldest political party Indian National Congress, founded in 1885, attempted to keep a distance from the socio-religious movements and identity politics.[387]

Indian Renaissance

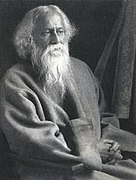

The Bengali Renaissance refers to a social reform movement, dominated by Bengali Hindus, in the Bengal region of the Indian subcontinent during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a period of British rule. Historian Nitish Sengupta describes the renaissance as having started with reformer and humanitarian Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1775–1833), and ended with Asia's first Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941).[388] This flowering of religious and social reformers, scholars, and writers is described by historian David Kopf as "one of the most creative periods in Indian history."[389]

During this period, Bengal witnessed an intellectual awakening that is in some way similar to the Renaissance. This movement questioned existing orthodoxies, particularly with respect to women, marriage, the dowry system, the caste system, and religion. One of the earliest social movements that emerged during this time was the Young Bengal movement, which espoused rationalism and atheism as the common denominators of civil conduct among upper caste educated Hindus.[390] It played an important role in reawakening Indian minds and intellect across the Indian subcontinent.

Famines

During British East India Company and British Crown rule, India experienced some of deadliest ever recorded famines. These famines, usually resulting from crop failures due to El Niño and often exacerbated by policies of the colonial government,[391] included the Great Famine of 1876–1878 in which 6.1 million to 10.3 million people died,[392] the Great Bengal famine of 1770 where between 1 and 10 million people died,[393][394] the Indian famine of 1899–1900 in which 1.25 to 10 million people died,[391] and the Bengal famine of 1943 where between 2.1 and 3.8 million people died.[395] The Third plague pandemic in the mid-19th century killed 10 million people in India.[396] Despite persistent diseases and famines, the population of the Indian subcontinent, which stood at up to 200 million in 1750,[397] had reached 389 million by 1941.[398]

World War I

During World War I, over 800,000 volunteered for the army, and more than 400,000 volunteered for non-combat roles, compared with the pre-war annual recruitment of about 15,000 men.[399] The Army saw action on the Western Front within a month of the start of the war at the First Battle of Ypres. After a year of front-line duty, sickness and casualties had reduced the Indian Corps to the point where it had to be withdrawn. Nearly 700,000 Indians fought the Turks in the Mesopotamian campaign. Indian formations were also sent to East Africa, Egypt, and Gallipoli.[400]

Indian Army and Imperial Service Troops fought during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign's defence of the Suez Canal in 1915, at Romani in 1916 and to Jerusalem in 1917. India units occupied the Jordan Valley and after the German spring offensive they became the major force in the Egyptian Expeditionary Force during the Battle of Megiddo and in the Desert Mounted Corps' advance to Damascus and on to Aleppo. Other divisions remained in India guarding the North-West Frontier and fulfilling internal security obligations.

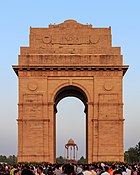

One million Indian troops served abroad during the war. In total, 74,187 died,[401] and another 67,000 were wounded.[402] The roughly 90,000 soldiers who died fighting in World War I and the Afghan Wars are commemorated by the India Gate.

World War II

British India officially declared war on Nazi Germany in September 1939.[403] The British Raj, as part of the Allied Nations, sent over two and a half million volunteer soldiers to fight under British command against the Axis powers. Additionally, several Indian Princely States provided large donations to support the Allied campaign during the War. India also provided the base for American operations in support of China in the China Burma India Theatre.

Indians fought with distinction throughout the world, including in the European theatre against Germany, in North Africa against Germany and Italy, against the Italians in East Africa, in the Middle East against the Vichy French, in the South Asian region defending India against the Japanese and fighting the Japanese in Burma. Indians also aided in liberating British colonies such as Singapore and Hong Kong after the Japanese surrender in August 1945. Over 87,000 soldiers from the subcontinent died in World War II.

The Indian National Congress, denounced Nazi Germany but would not fight it or anyone else until India was independent. Congress launched the Quit India Movement in August 1942, refusing to co-operate in any way with the government until independence was granted. The government was ready for this move. It immediately arrested over 60,000 national and local Congress leaders. The Muslim League rejected the Quit India movement and worked closely with the Raj authorities.

Subhas Chandra Bose (also called Netaji) broke with Congress and tried to form a military alliance with Germany or Japan to gain independence. The Germans assisted Bose in the formation of the Indian Legion;[404] however, it was Japan that helped him revamp the Indian National Army (INA), after the First Indian National Army under Mohan Singh was dissolved. The INA fought under Japanese direction, mostly in Burma.[405] Bose also headed the Provisional Government of Free India (or Azad Hind), a government-in-exile based in Singapore.[406][407] The government of Azad Hind had its own currency, court, and civil code; and in the eyes of some Indians its existence gave a greater legitimacy to the independence struggle against the British.[citation needed]

By 1942, neighbouring Burma was invaded by Japan, which by then had already captured the Indian territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Japan gave nominal control of the islands to the Provisional Government of Free India on 21 October 1943, and in the following March, the Indian National Army with the help of Japan crossed into India and advanced as far as Kohima in Nagaland. This advance on the mainland of the Indian subcontinent reached its farthest point on Indian territory, retreating from the Battle of Kohima in June and from that of Imphal on 3 July 1944.

The region of Bengal in British India suffered a devastating famine during 1940–1943. An estimated 2.1–3 million died from the famine, frequently characterised as "man-made",[408] with most sources asserting that wartime colonial policies exacerbated the crisis.[409]

Indian independence movement (1885–1947)

The numbers of British in India were small,[412] yet they were able to rule 52% of the Indian subcontinent directly and exercise considerable leverage over the princely states that accounted for 48% of the area.[413]

One of the most important events of the 19th century was the rise of Indian nationalism,[414] leading Indians to seek first "self-rule" and later "complete independence". However, historians are divided over the causes of its rise. Probable reasons include a "clash of interests of the Indian people with British interests",[414] "racial discriminations",[415] and "the revelation of India's past".[416]

The first step toward Indian self-rule was the appointment of councillors to advise the British viceroy in 1861 and the first Indian was appointed in 1909. Provincial Councils with Indian members were also set up. The councillors' participation was subsequently widened into legislative councils. The British built a large British Indian Army, with the senior officers all British and many of the troops from small minority groups such as Gurkhas from Nepal and Sikhs.[417] The civil service was increasingly filled with natives at the lower levels, with the British holding the more senior positions.[418]

Bal Gangadhar Tilak, an Indian nationalist leader, declared Swaraj (home rule) as the destiny of the nation. His popular sentence "Swaraj is my birthright, and I shall have it"[419] became the source of inspiration for Indians. Tilak was backed by rising public leaders like Bipin Chandra Pal and Lala Lajpat Rai, who held the same point of view, notably they advocated the Swadeshi movement involving the boycott of all imported items and the use of Indian-made goods;[420] the triumvirate were popularly known as Lal Bal Pal. Under them, India's three big provinces – Maharashtra, Bengal and Punjab shaped the demand of the people and India's nationalism.[citation needed] In 1907, the Congress was split into two factions: The radicals, led by Tilak, advocated civil agitation and direct revolution to overthrow the British Empire and the abandonment of all things British. The moderates, led by leaders like Dadabhai Naoroji and Gopal Krishna Gokhale, on the other hand, wanted reform within the framework of British rule.[420]

The partition of Bengal in 1905 further increased the revolutionary movement for Indian independence. The disenfranchisement lead some to take violent action.

The British themselves adopted a "carrot and stick" approach in recognition of India's support during the First World War and in response to renewed nationalist demands. The means of achieving the proposed measure were later enshrined in the Government of India Act 1919, which introduced the principle of a dual mode of administration, or diarchy, in which elected Indian legislators and appointed British officials shared power.[421] In 1919, Colonel Reginald Dyer ordered his troops to fire their weapons on peaceful protestors, including unarmed women and children, resulting in the Jallianwala Bagh massacre; which led to the Non-cooperation Movement of 1920–1922. The massacre was a decisive episode towards the end of British rule in India.[422]

From 1920 leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi began highly popular mass movements to campaign against the British Raj using largely peaceful methods. The Gandhi-led independence movement opposed the British rule using non-violent methods like non-co-operation, civil disobedience and economic resistance. However, revolutionary activities against the British rule took place throughout the Indian subcontinent and some others adopted a militant approach like the Hindustan Republican Association, founded by Chandrasekhar Azad, Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev Thapar and others, that sought to overthrow British rule by armed struggle.

The All India Azad Muslim Conference gathered in Delhi in April 1940 to voice its support for an independent and united India.[423] Its members included several Islamic organisations in India, as well as 1400 nationalist Muslim delegates.[424][425][426] The pro-separatist All-India Muslim League worked to try to silence those nationalist Muslims who stood against the partition of India, often using "intimidation and coercion".[425][426] The murder of the All India Azad Muslim Conference leader Allah Bakhsh Soomro also made it easier for the pro-separatist All-India Muslim League to demand the creation of a Pakistan.[426]

After World War II (c. 1946–1947)

— From, Tryst with destiny, a speech given by Jawaharlal Nehru to the Constituent Assembly of India on the eve of independence, 14 August 1947.[427]

In January 1946, several mutinies broke out in the armed services, starting with that of RAF servicemen frustrated with their slow repatriation to Britain. The mutinies came to a head with mutiny of the Royal Indian Navy in Bombay in February 1946, followed by others in Calcutta, Madras, and Karachi. The mutinies were rapidly suppressed. Also in early 1946, new elections were called and Congress candidates won in eight of the eleven provinces.

Late in 1946, the Labour government decided to end British rule of India, and in early 1947 it announced its intention of transferring power no later than June 1948 and participating in the formation of an interim government.

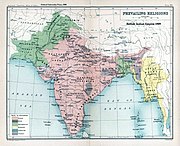

Along with the desire for independence, tensions between Hindus and Muslims had also been developing over the years. The Muslims had always been a minority within the Indian subcontinent, and the prospect of an exclusively Hindu government made them wary of independence; they were as inclined to mistrust Hindu rule as they were to resist the foreign Raj.

Muslim League leader Muhammad Ali Jinnah proclaimed 16 August 1946 as Direct Action Day, with the stated goal of highlighting, peacefully, the demand for a Muslim homeland in British India, which resulted in the outbreak of the cycle of violence that would be later called the "Great Calcutta Killing of August 1946". The communal violence spread to Bihar (where Muslims were attacked by Hindus), to Noakhali in Bengal (where Hindus were targeted by Muslims), in Garhmukteshwar in the United Provinces (where Muslims were attacked by Hindus), and on to Rawalpindi in March 1947 in which Hindus were attacked or driven out by Muslims.

Independence and partition (c. 1947–present)

In August 1947, the British Indian Empire was partitioned into the Union of India and Dominion of Pakistan. In particular, the partition of Punjab and Bengal led to rioting between Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs in these provinces and spread to other nearby regions, leaving some 500,000 dead. The police and army units were largely ineffective. The British officers were gone, and the units were beginning to tolerate if not actually indulge in violence against their religious enemies.[428][429][430] Also, this period saw one of the largest mass migrations anywhere in modern history, with a total of 12 million Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims moving between the newly created nations of India and Pakistan (which gained independence on 15 and 14 August 1947 respectively).[429] In 1971, Bangladesh, formerly East Pakistan and East Bengal, seceded from Pakistan.[431]

Historiography

In recent decades there have been four main schools of historiography in how historians study India: Cambridge, Nationalist, Marxist, and subaltern. The once common "Orientalist" approach, with its image of a sensuous, inscrutable, and wholly spiritual India, has died out in serious scholarship.[432]

The "Cambridge School", led by Anil Seal,[433] Gordon Johnson,[434] Richard Gordon, and David A. Washbrook,[435] downplays ideology.[436] However, this school of historiography is criticised for western bias or Eurocentrism.[437]

The Nationalist school has focused on Congress, Gandhi, Nehru and high level politics. It highlighted the Mutiny of 1857 as a war of liberation, and Gandhi's 'Quit India' begun in 1942, as defining historical events. This school of historiography has received criticism for Elitism.[438]

The Marxists have focused on studies of economic development, landownership, and class conflict in precolonial India and of deindustrialisation during the colonial period. The Marxists portrayed Gandhi's movement as a device of the bourgeois elite to harness popular, potentially revolutionary forces for its own ends. Again, the Marxists are accused of being "too much" ideologically influenced.[439]

The "subaltern school", was begun in the 1980s by Ranajit Guha and Gyan Prakash.[440] It focuses attention away from the elites and politicians to "history from below", looking at the peasants using folklore, poetry, riddles, proverbs, songs, oral history and methods inspired by anthropology. It focuses on the colonial era before 1947 and typically emphasises caste and downplays class, to the annoyance of the Marxist school.[441]

More recently, Hindu nationalists have created a version of history to support their demands for Hindutva ('Hinduness') in Indian society. This school of thought is still in the process of development.[442] In March 2012, Diana L. Eck, professor of Comparative Religion and Indian Studies at Harvard University, authored in her book India: A Sacred Geography, that the idea of India dates to a much earlier time than the British or the Mughals; it was not just a cluster of regional identities and it was not ethnic or racial.[443][444][445][446]

![The first session of the Indian National Congress in 1885. A. O. Hume, the founder, is shown in the middle (third row from the front). The Congress was the first modern nationalist movement to emerge in the British Empire in Asia and Africa.[410]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/bb/1st_INC1885.jpg/140px-1st_INC1885.jpg)

![From the late 19th century, and especially after 1920, under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi (right), the Congress became the principal leader of the Indian independence movement.[411] Gandhi is shown here with Jawaharlal Nehru, later the first prime minister of India.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9e/Nehru_gandhi.jpg/140px-Nehru_gandhi.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment